#devops #infrastructure-as-code #aws

Authenticating to AWS the right way for (almost) every use-case

Published Sep 5, 2022 by Lee Briggs

One of my favourite things about AWS is their ability to make the wrong decision easy and the right decision hard. Our world is moving towards managed services and “off the shelf” experiences for provisioning infrastructure and deploying applications. AWS itself has gotten the memo with its introduction of services like AWS Proton, however its real value proposition is in its ability to provider building blocks for the infrastructure needs of today.

It largely does a good job of providing these building blocks, but where it really falls down is in the “reasonable defaults” category with most services. Nowhere is this more obvious than in its authentication strategy.

Authentication vs Authorization

Before I go off into a rant about why AWS authentication is broken by default, I’d like to talk about where AWS Identity and Access Manager’s responsibilities lie. The same service, IAM, is largely responsible for both authentication and authorization within AWS. Let’s define those before we explain IAM’s role.

Authentication is the mechanism by which you tell a service who you are. The most common form of authentication is a username and password, but there are many other ways of providing authentication like AWS access keys and secret keys. You send your credentials over to a service and it verifies those credentials are correct. As an aside here, one of the biggest problems with the internet is that credentials are designed to verify who you are but don’t actually verify the person owning the credentials is the person who’s supposed to. Multi-factor authentication is designed to help with this, but there’s still lots of room for improvement.

Authorization is the way the service knows what you’re allowed to do. An AWS IAM policy is a document that give you the ability to dictate that once someone or something has authenticated to AWS, this is the actions they’re allowed to perform.

I have a lot of time for AWS authorization via IAM policies because they’re extremely verbose and operate on a whitelisting basis, meaning by default you can’t really do anything at all.

However, the “default” mechanism for providing access to AWS is absolutely shit. Here’s why.

The AWS Credential Problem

If you’re a user of AWS, you probably have an AWS Access Key or AWS Secret Key stored on your machine right now. Go on, take a look in ${HOME}/.aws/credentials and have a look if you have them. Do you? That’s bad.

If you don’t have AWS credentials on your personal laptop, bust open your companies flagship application and do a quick search for AWS_ACCESS_KEY. Do you see anything? That’s really fucking bad.

If you answered yes to either of these, it’s best to keep reading. If you answered no, keep reading anyway.

Credential Rotation

The reason it’s bad is simple: static credentials are very easy to steal or extract for an attacker. There are lots of ways this can happen: you could leave your laptop on a train (if you live in a civilized country with access to public transit). You could accidentally check them into version control on the public internet. You might even accidentally blurt them out to someone while in a bar instead of your phone number if you’ve memorized them for some reason. However you choose to tell the world about your authentication keys for AWS, the impact is the same: those keys then need to be manually revoked by you because they have an unlimited lifespan.

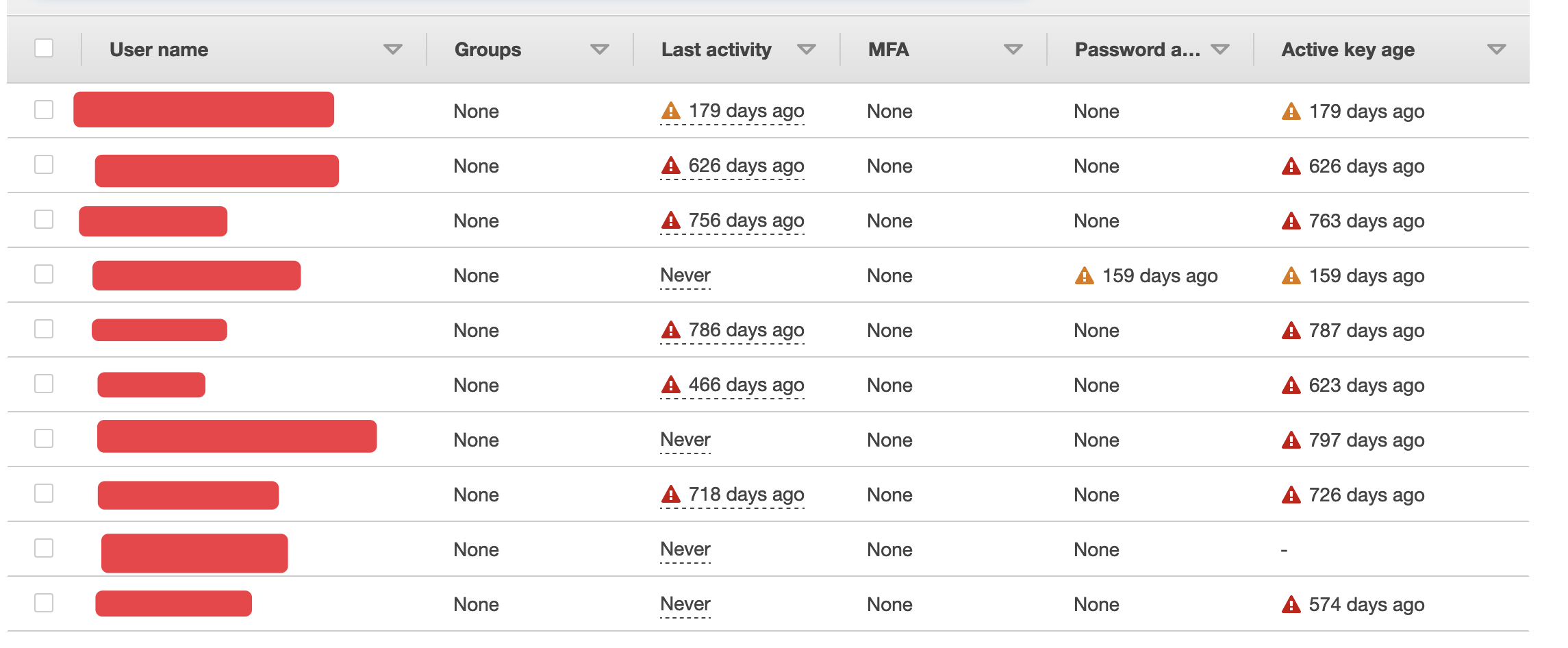

The general solution to this problem is to regularly rotate your IAM credentials. AWS tries to do its best to make you do this by shaming you on the AWS Users page:

The problem with rotating these credentials is that it’s such a bloody faff. You have to update the keys wherever they’re used and stuff might break when you’re doing it and I really just can’t be arsed, what’s the worst that could happen?

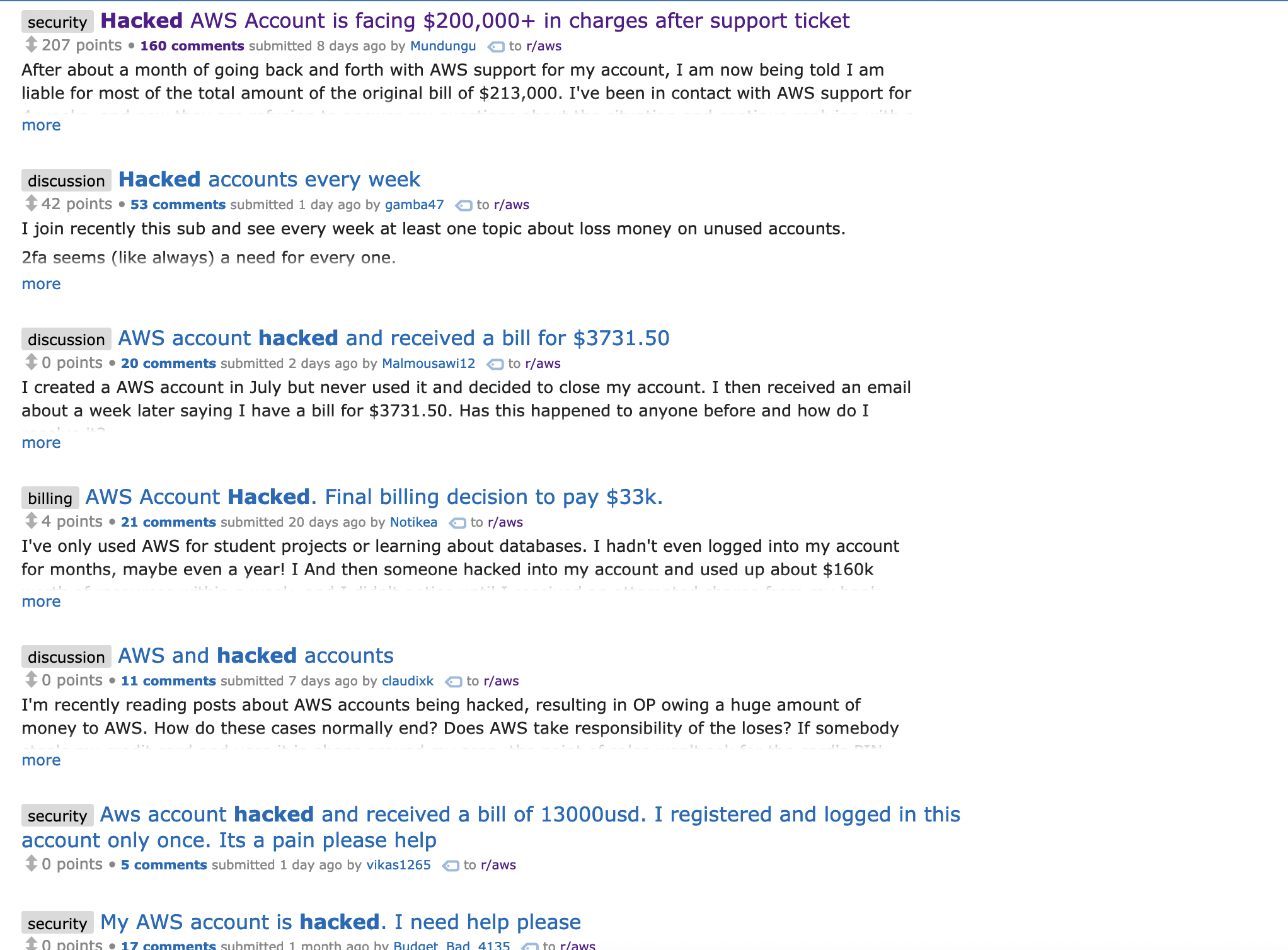

Well the answer is that it could cost you a lot of your money or your companies money as this lovely Reddit search of the AWS subreddit shows:

If you head into Reddit’s cesspit for a second and read one of those threads, you’ll see the advice to “make sure you have MFA turned on!” which is very good advice. The problem is, AWS access keys and secret keys don’t need MFA to be effective. If someone has your keys, they can do a whole bunch of stuff, including change your password to lock you out. That’s not good, is it?

Temporary Credentials to the rescue

The obvious solution to this is to just not use AWS Access Keys or Secret Keys, but you still need to authenticate to the AWS API to tell it who you are! Luckily, AWS has a solution for this in the form of Temporary Credentials

Session Tokens

AWS can provide you with an AWS Access Key and an AWS secret key via AWS STS, its security token service. Credentials generated via STS are very similar to the tokens you see in the AWS IAM User interface, but they also come with an AWS Session Token which requires you to specify duration. Once that duration has expired, the issued credentials become inactive and can’t be used, so you now need to generate some more.

Hang on…

Yes, that’s right. You’ll have AWS credentials you have to constantly renew in order for them to be effective. You also need to have already authenticated with AWS to retrieve temporary credentials! If this sounds like a lot of work with a very limited amount of benefit, read on.

Back to Authentication

I started off making the point that AWS makes the right thing hard to do, and in the case of temporary credentials, the difficulty comes in knowing what the hell is the right thing to do. AWS makes it really fucking easy to generate long standing AWS credentials, in a lot of ways, the default for AWS is to use AWS IAM Users. It doesn’t tell you about all the alternatives to IAM users, when to use them and how to implement them at all.

While it may or may not be clear to you that temporary credentials provide a huge security benefit, what may not be clear at this stage is how the hell you actually generate them.

The answer to that largely depends on your current use case. Generating temporary credentials is different depending on if you’re a human, machine or application. So now I’ve spent the better part of this post explaining things you probably don’t care about like an online recipe that makes you scroll for 10 minutes, lets actually talk about the different strategies for authenticating to AWS.

I want to..

From here, we’re going to detail the scenarios in the form of user stories, because everyone loves those in their JIRA tickets don’t they?

Authenticate to AWS as a Human User

As a human user, the temptation is there to generate AWS keys via the IAM user interface. That’s wrong. You should be using AWS IAM Identity Center aka the artist formerly known as AWS SSO.

AWS SSO allows you to either use AWS as an identity provider, or hook in your own identity provider like Okta, Auth0 or even Google. Any service that provides services as an Identity Provider (or IdP) can be hooked into AWS IAM Identity Center.

Once you’ve hooked in your IdP or enabled AWS’s IdP, you then use the AWS CLI to authenticate via aws sso login.

You’ll need to configure your AWS configuration file a little bit, mainly to tell it what AWS account and role you want when you login:

[profile personal-management]

sso_start_url = https://lbrlabs.awsapps.com/start

sso_region = us-west-2

sso_account_id = <account-id>

sso_role_name = AWSAdministratorAccess

region = us-west-2

output = json

Once you run aws sso login for that profile, the AWS CLI will walk you through the authentication flow, verify who you are and then issue temporary credentials for you!

These temporary credentials get stored inside ~/.aws/sso/cache and will expire within a duration you specify at the AWS IAM Identity Center level. Generally you will have to reauthenticate once a day via aws sso login, but that’s good because it means if anyone steals your temporary credentials, they will automatically expire after a certain time period.

Once you’re authenticated via SSO, you can also generate new temporary credentials using this handly little tool I wrote once upon a time.

Authenticate to AWS as an EC2 Instance

Hopefully this one is straightforward, but if you’re running workloads inside anything that uses an EC2 Instance, whether that be an unmanaged EC2 instance like EC2 itself, or via a managed service like Fargate, you should be assigning an IAM role and possible an Instance Profile.

Assigning a role to your AWS workload will automatically mean credentials get refreshed for you on a time period. You no longer have hard coded AWS credentials stored in plaintext that can be extracted and used elsewhere. Easy!

Authenticate to AWS as an application that only managed content in an S3 bucket

This one’s a little unique. Let’s say you have an application that uses object storage, and you want to keep those files private from the internet, but you want people to be able to manage files. A good example? Something that allows you to upload a profile photo might fit the bill.

You probably don’t want to generate AWS credentials for each user session, and you definitely don’t want to allow anyone to mess with your S3 bucket (although, lots of people do that. They usually make the news when they do..).

So AWS obviously came up with a solution to this! Presigned URLs!

Presigned URLs generate a unique link to an object within an S3 bucket that expires. There are no temporary credentials, but the URL itself has credentials embedded in it, like this:

https://thisisntarealbucket.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/image.png?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=<AWS_ACCESS_KEY>%2F20180210%2Feu-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=202000905T171315Z&X-Amz-Expires=1800&X-Amz-Signature=12b74b0794aa147ad7d3d03b3f20c61f1f91cc9ad8873e3314255dc479a25351&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host

This has a limited number of use cases, but is incredibly important for the use cases where it comes up. If you think you might need to let users upload or manage objects in a bucket, go with this option where you can.

Authenticate to AWS as a CI/CD Pipeline

As with human users mentioned earlier, it can be incredibly tempting to just generate an IAM user and an Access Key and Secret Key and stick them in the secrets mechanism your CI/CD tool has.

There is another way!

OIDC Providers give you the capability to authenticate to AWS via the OpenIdentity Connect Protocol.

I wrote about this extensively if you’re using GitHub Actions and AWS (as well as other cloud providers), but the reality is that lots of CI/CD tools like GitLab and CircleCI.

If your CI/CD tool doesn’t support OIDC, you should change CI/CD tools. There’s shitloads of them, choose one that does things properly, will you?

Authenticate to AWS as compute I manage that isn’t running inside AWS

The final authentication strategy is one I never thought I’d see materalize. In this scenario, perhaps you’re running compute in another cloud provider or in an on-premises datacenter. If you have the ability to run an operating system daemon you can use the imaginatively named IAM Role Anywhere.

IAM roles anywhere expects you to provision a valid TLS (X.509) certificate and create a trust (via a trust anchor) in AWS.

Once you’ve trusted AWS with your infrastructure, you can then use a credential process to issue some temporary credentials. Once upon a time, none of this was possible and you’d have to manually mess around rotating credentials, but now you get to mess around with Certificate Authorities instead. Is this better? Well, for the purposes of this blog post, lets say it is.

Wrap Up

I think I’ve covered a most of the needs here and given you at the very least, something to Google when you’re in a certain situation and need some AWS credentials. If you think I missed an option, let me know on Twitter.

If you need help implementing any of these strategies, why not Get in Touch!

© 2021, Ritij Jain | Pudhina Fresh theme for Jekyll.