#devops #infrastructure-as-code #pulumi #terraform #crossplane #cloudformation #arm

IaC Ergonomics: Choosing an Infrastructure as Code Tool

Published Aug 26, 2022 by Lee Briggs

This is long. What’s the TL;DR?

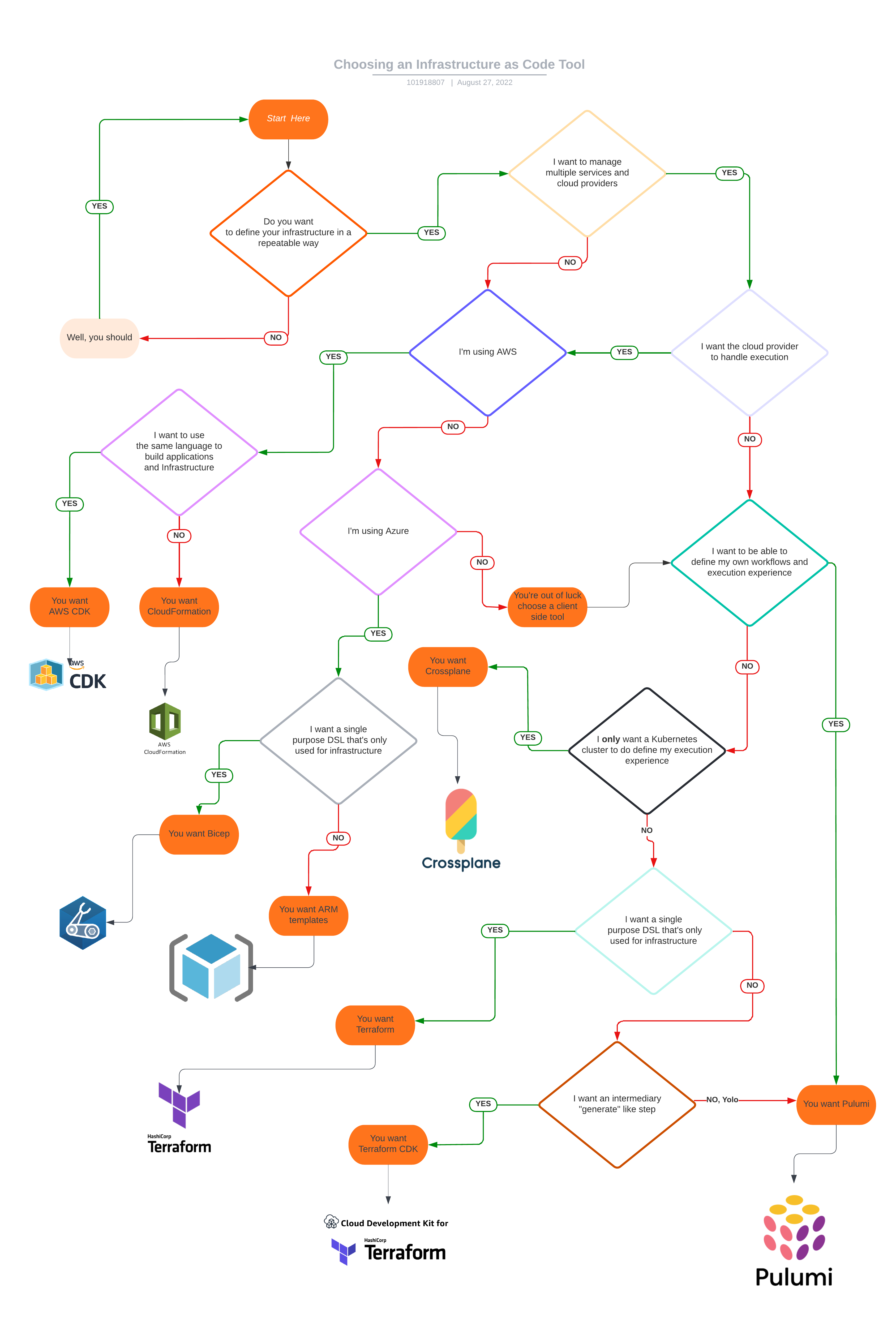

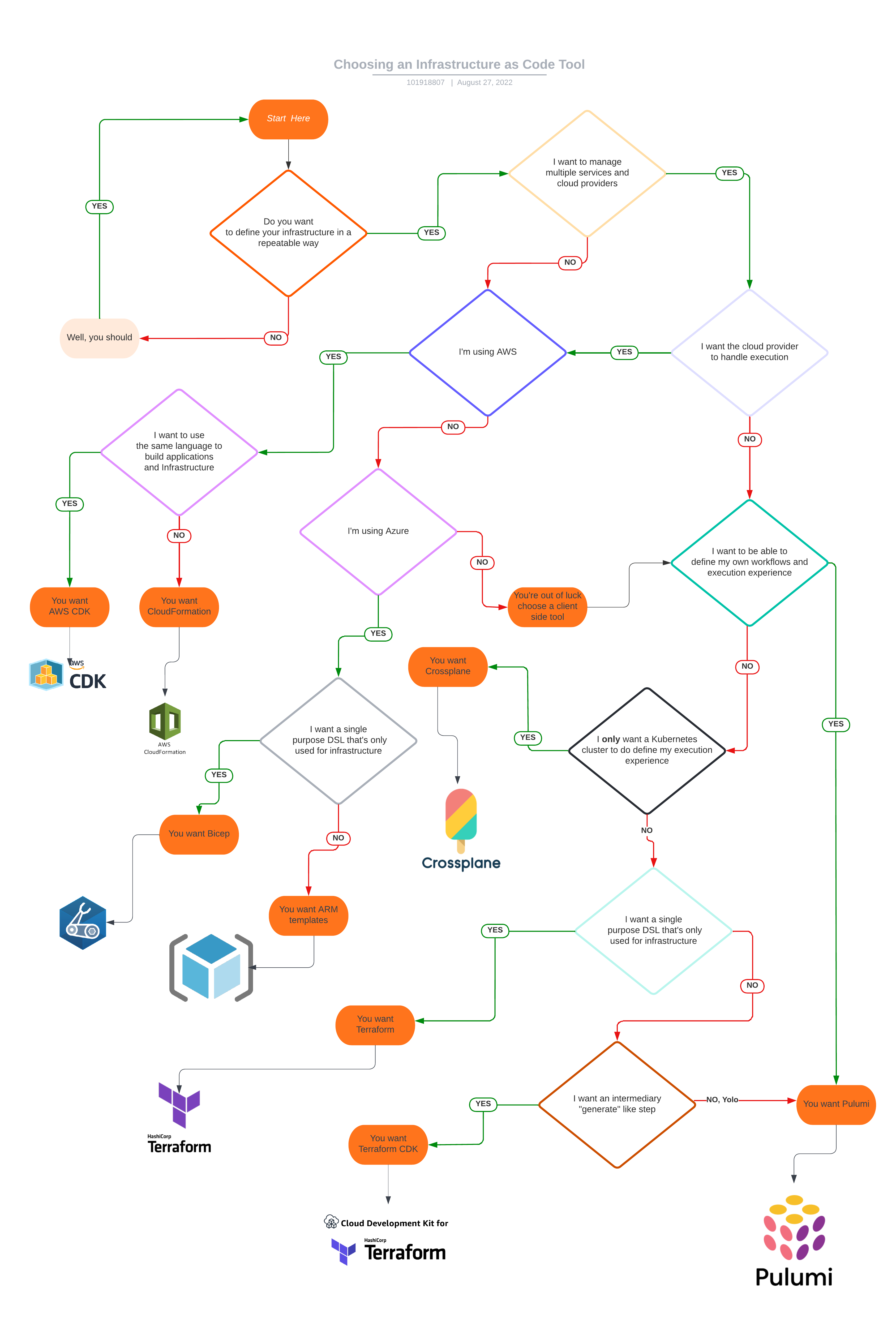

I made a decision tree to help you decide what Infrastructure as Code tool you should use

But you need to read the whole thing to use it properly. Stop being lazy.

Infrastructure as Code Comparisons

As a person with more than a vested interest in the Infrastructure as Code market, I see a whole lot of conversations in the public sphere about choosing solution. I’ll often see people having discussions about their favourite tool on Twitter, Reddit or <insert other online platform here> and undoubtedly come across a lot of strong opinions.

I have strong opinions myself. They’re so strong I joined an Infrastructure as Code startup because I believed in the product. Hell, I sell the damn thing to people. As a result, I have to be hyper focused on the way our product and our competitor’s products change, and need to be able to speak to the value of them in order to try and understand what’s going through a user’s mind.

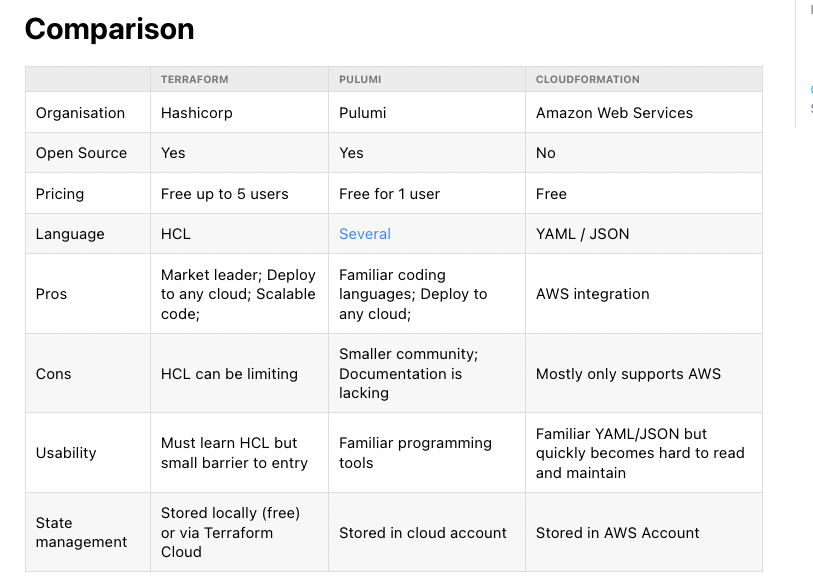

A common pattern I’ve seen as the industry has evolved and new competitors have joined the growing market is the habit of creating an article that compares features of the tools. These often look like this:

Now, if you’re comparing two or three tools, a comparison table can often be helpful, but it’s my personal unsolicited opinion that these tables are useless.

- They don’t help a prospective user understand the value of the tools.

- They don’t cover the massive, broad capabilities of the tools.

- They don’t actually cover the options available to you.

- They’re often out of date as soon as you publish them.

If you’re unfortunate enough to have had this post come across your screen, ask yourself the question: If I saw this table, would it help me choose an Infrastructure as Code tool? If the answer is yes, close the tab and move on with your life. If the answer is “no” then keep reading, because I’m going for something different.

Defining Infrastructure as Code Ergonomics

While features are undoubtedly important to any user, I’ve discovered that people generally want to boil down their Infrastructure as Code choices down to the experience they’re going to have when using the tool. Programming languages have the concept of “language ergonomics” which helps to define the friction you experience while trying to get things done using the tool, and considering we’ve decided that we’re going to define our Infrastructure as Code it seems fair to consider the ergonomics of the tool.

Now, ergonomics is ultimately a subjective thing: everyone will have a different experience while using the different IaC tools available. In order to try and bring some objectivity to the matter, I’m going to break down Infrastructure as Code ergonomics into 3 distinct experience.

The Authoring Experience

The authoring experience is defined as what mechanisms you have at your disposal to express your infrastructure. We already decided in my last post that generally, Infrastructure as Code tools have settled on the idea that they’re declarative, and what’s important is your ability to manipulate the way the declarative graph is built. There are 3 main camps that have been defined for the authoring experience:

Domain Specific Languages

A domain specific language is what it sounds like: a language defined specifically for that domain.

DSLs often have a shallow learning curve, and are built specifically for that purpose meaning they are often well suited to the purpose. They are often not Turing complete on their own and have a “ceiling” in terms of how expressive they are.

Some people will argue that DSLs are favourable for Infrastructure as Code because they prevent you from creating complexity because of that limited expressiveness. Those people are wrong, because ultimately badly written DSL code is just as complex and hard to refactor and understand as badly written code in a general purpose language, but I’ve found people are very very willing to die on that hill.

Programming Languages

Programming languages are the language(s) you know and love from application development or scripting. Python, TypeScript, Go, Java and many more are options in the Infrastructure as Code space, and they all bring their own toolchains, syntax and idiosyncrasies.

Programming languages are flexible, well understood in the industry (we build applications with them!), well supported by development tools and processes and have large ever growing communities behind them. You’ll often find that if you’re using an IDE in general development, your IDE gives you a lot of extra support and functionality beyond scribbling your infrastructure into a word document and hoping you didn’t make any mistakes.

However, programming languages have a slightly higher learning curve than DSLs. This increase in complexity brings with it a dramatic increase in expressibility and control. Again, some people don’t think this is a good thing but my experience has been that those people are just scared of programming languages.

Personally, I believe the Infrastructure as Code industry is trending the way of programming languages by default for the authoring experience for 2 reasons:

- What you learn is reusable in other functions, like application development

- Infrastructure is complicated, so you need the ability to represent it correctly when defining it.

Most of the major Infrastructure as Code tools have invested some time in a programming language authoring model at this point, so the winds seem to be changing.

Personally, I believe this to be a good thing. Using a language with a first class type system and IDE support is, in my opinion, the “correct” way to define your infrastructure. I’ve written before about how if you’re not functional as a software developer and see yourself more as a “sysadmin” type, defining infrastructure in a programming language can level up your career because you’re learning the language through the lense of something you already know instead of blindly running create-react-app and hoping for the best.

If you’re an application developer you likely already know a programming language, and now you get to learn Infrastructure as Code through the lense of something you know - the language.

As I mentioned in the DSL section, naysayers will tell you that programming languages have too much “power” for infrastructure and the increased flexibility that comes with a programming language means that people can make things too hard to maintain and manage. Again, this is true of any software and language, but I won’t spend all of this post arguing with people who don’t want to see the way the industry is going hurtling towards them.

Configuration Languages

The last option is configuration languages. These have the least amount of expressibility, and usually need a templating language bolted on top to create any ability to get your job done. We’ve already decided that’s completely fucking stupid, so I won’t say any more about that.

The Execution Experience

Once you’ve defined your infrastructure using the authoring experience, you’ll then need to let your cloud provider know about what you’ve written. I’m defining this as the execution experience. There are a few different options in this space.

Client Side Experience

The client side experience - you run a command line tool which talks to an API. You might run it from your personal machine or from a CI/CD pipeline, but ultimately you’re responsible for that. The graph is built locally by the tool.

With local execution experience, the tool will almost always need some mechanism to store its state. The state storage models differ by tool, and is generally where the open source tools start to embrace monetization. The necessity to have a state store comes from the need to compare the current state of the world (ie: what exists in the cloud provider) with the code you’ve written during the authoring model stage.

People will often argue that introducing state storage adds complexity and management overhead, but the tools have evolved significantly to the point where state storage becomes less of a problem. I’ll talk more about this when I examine the tools themselves.

Server Side Experience

The server side experience is the practice of handing off the execution to your cloud provider. You dispatch your authored IaC off to the cloud providers service, and it takes care of building a graph for you and managing how it runs.

This removes the need for state storage, but also completely removes your ability to manipulate the workflow and how it executes. You have zero control over prioritization, you can’t speed it up (or slow it down, if necessary) and you have very little control over the feedback loop for your developers.

The Unique Experience

Most Infrastructure as Code tools fall into the above two categories, but Pulumi has a fairly unique mechanism that separates it from all of the above. I’ll call this the “choose your own adventure” experience which is sort of an extension of the client side experience. More information on that when we examine Pulumi in-depth.

The Cloud Provider Experience

The final experience I’ll define is the cloud provider experience. This is as simple as defining which cloud providers the tool supports and how support for cloud provider APIs is added to the respective tools. There are two camps to choose from.

Multi Cloud Support

Multi cloud support - The tool allows you to interact with multiple cloud providers and often pass values from one cloud provider to another. If you define a load balancer in AWS, you can pass the resulting address from that to Cloudflare, for example.

Tools that support multiple clouds can often have differing levels of support for the varying APIs that are added. Cloud providers are continuously adding new features, and it’s often up to the Infrastructure as Code tool, or their respective community to add those features.

Single Cloud Support

With single cloud support, the tool only gives a shit about the cloud that provides it. Advocates of CloudFormation will often exclaim that you can extend the single cloud tools out to other clouds, but in practice nobody does that because it’s a ridiculous maintenance burden nobody wants to undertake.

What’s alluring about the tools that focus on a single cloud is that new features are often available very quickly for that tool. If AWS adds a brand new tool called AWS System Manager for Management of Systems in Management, it will (often) add support for it on launch day. This isn’t always the case for multi cloud tools.

Personally, I can’t ever see why I’d use a single cloud tool, not because I’d advocate for a multi cloud strategy for compute, but mainly because I want the choice to choose another DNS provider or monitoring tool. I want to be able to manage everything from my cloud provider, to my version control repositories with Infrastructure as Code. Ultimately though, you do you.

The Choices

Now we’ve defined the ergonomics, we need to bring in all of the contenders and see where they fit within these experiences. Let’s have a look!

Terraform

Terraform has been around since 2014, and was created by HashiCorp. As a side note, I was lucky enough to be a user of Terraform 0.1. I’m also fortunate enough to regularly work and socialize with people who defined the way Terraform works and operates and contributed thousands of lines of code to it.

The Authoring Experience

The primary Terraform authoring experience is HCL. The original incarnation of HCL was quite rigid, didn’t support abstractions or have mechanisms to create loops or use conditionals. The language is still evolving but as with all DSLs, it’s got a single purpose: You define infrastructure with it.

Lot’s of people love HCL. I don’t, but I promised this post would be reasonably objective, so I won’t expand on why.

# a AWS route53 record defined in HCL

resource "aws_route53_record" "www" {

zone_id = aws_route53_zone.primary.zone_id

name = "www.example.com"

type = "A"

ttl = 300

records = [aws_eip.lb.public_ip]

}

Terraform has invested a lot of effort into a programming language authoring experience it calls CDK for Terraform which enables users to get the programming language authoring experience. Interestingly, if you examine the Terraform roadmap from 2021, most of the conversation is around CDK for Terraform, and there is seemingly very little investment in HCL. Make of that what you will.

// an ACM certificate defined in CDK with TypeScript

const cert = new acm.AcmCertificate(this, "cert", {

domainName,

validationMethod: "DNS",

provider,

});

The CDK for Terraform mechanism is an authoring experience for creating configuration based artifacts in that you run cdk synth before execution, which creates a set of files which Terraform then applies during the execution experience.

The Execution Experience

The execution experience of Terraform centres around the Terraform CLI, the managed service offerings for Terraform help you abstract that way from the end user. Using Terraform Cloud will mean you don’t have to define a CI/CD pipeline, but ultimately, you’re going to follow a CLI driven workflow.

$ terraform apply

data.aws_ram_resource_share.shared_services: Reading...

module.vpc.aws_vpc.this[0]: Refreshing state... [id=vpc-04b345ea3bdee4bd0]

module.vpc.data.aws_iam_policy_document.flow_log_cloudwatch_assume_role[0]: Reading...

module.vpc.data.aws_iam_policy_document.vpc_flow_log_cloudwatch[0]: Reading...

module.vpc.aws_eip.nat[0]: Refreshing state... [id=eipalloc-055ed15aa65be7222]

module.vpc.aws_vpc_dhcp_options.this[0]: Refreshing state... [id=dopt-06057da9905f3e077]

module.vpc.data.aws_iam_policy_document.flow_log_cloudwatch_assume_role[0]: Read complete after 0s [id=1021377347]

There is a programming language SDK wrapper mechanism for Terraform called terraform-exec but it’s only available in the Go progamming. If you want to build custom workflows for Terraform outside Go, you’re on your own.

The Cloud Provider Experience

The Terraform Registry has many many supported providers, at this stage if you think you need to support an API it probably has a Terraform provider. The registry also contains a whole host of abstractions in the form of modules which will help you define and build your infrastructure - there’s a whole bunch of “prior art” out there that’ll help you get off the ground.

CloudFormation

CloudFormation, arguably the OG infrastructure as code tool, is Amazon’s mechanism for deploying AWS resources.

Authoring Experience

CloudFormation has two supported authoring experiences, and a few years ago it would have been easy to say which was the “default”. The configuration language authoring experience is interesting - you author your CloudFormation templates in YAML or JSON but there’s internal CloudFormation functions which seem very DSL like.

This creates something of a learning curve, but it’s still relatively low as you’d expect from a configuration language authoring experience.

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: 2010-09-09

Description: Create an S3 Bucket

Resources:

S3Bucket:

Type: AWS::S3::Bucket

Description: Example Bucket

Properties:

BucketName: my-bucket

Outputs:

S3Bucket:

Description: Bucket Created using this template.

Value: !Ref S3Bucket

AWS has invested a lot of time and resources into it’s programming language based authoring experience: AWS Cloud Development Kit (AWS CDK).

It supports a variety of programming languages like TypeScript, Java, Python, Go and C# and it has an abstraction mechanism and library called constructs which act as best practice implementations for a variety of AWS use cases.

ec2_inst = aws_ec2.Instance(

self, 'example',

instance_name=self.instance_name,

instance_type=instance_type,

machine_image=ami_image,

vpc=vpc,

security_group=sec_grp)

The construct library is broad, robust and well supported and covers many of needs you’d have to launching infrastructure from simple to complex.

AWS CDK has many of the same pros and cons of other programming language based approaches, a need to understand the ecosystem and the language syntax but a huge improvement in skill reusability.

Like Terraform CDK, AWS CDK has an intermediary cdk synth step which creates a bunch of configuration language based artifacts.

Execution Experience

Once you have your CDK or manually authored CloudFormation templates, you send them off the CloudFormation and it does the execution for you.

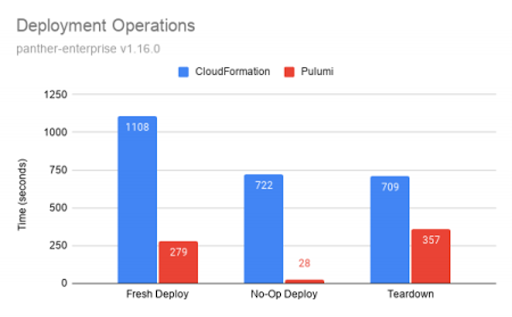

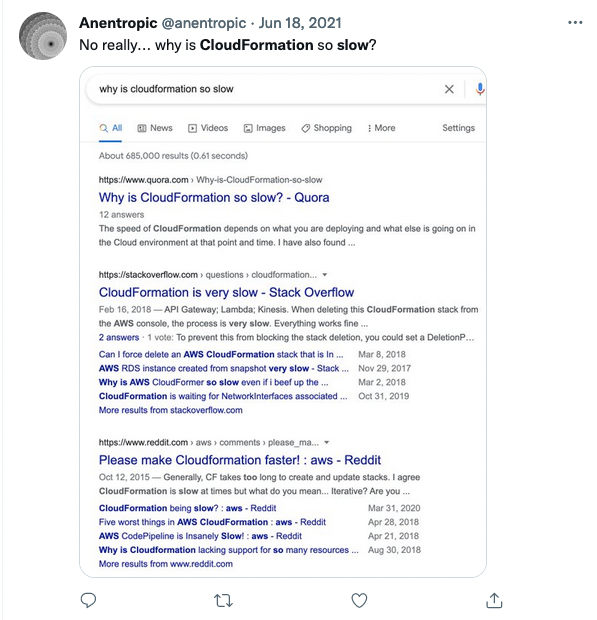

CloudFormation is really, really slow against a client side execution experience.

Don’t believe me though, just search on Twitter for other people’s experiences:

You can’t really do much about this. It just..is.

Cloud Provider Experience

CloudFormation is strictly AWS only. Diehard fans will tell you that CloudFormation supports “custom resources” that allow you to manage non AWS resources, but it’s really not fun and I’ve never met anyone masochistic enough to actually do it at scale.

The AWS only nature of it might be workable for you if you’re fully bought into the AWS landscape, but if you’re using an external monitoring mechanism, or another DNS provider, you’re shit out of luck.

Crossplane

Crossplane is a relative newcomer to the infrastructure as code space that focuses entirely on using Kubernetes as its execution mechanism. It’s owned and managed by Upbound.

Authoring Experience

The tight coupling with Kubernetes means that Crossplane’s primary authoring experience is YAML, a configuration based authoring experience. Resources are defined in a Kubernetes manifest which can be JSON if that’s your flavour of configuration hell.

# Provision a Google Cloud Firewall in Google Cloud

apiVersion: compute.gcp.crossplane.io/v1alpha1

kind: Firewall

metadata:

name: example

spec:

forProvider:

allowed:

- IPProtocol: tcp

ports: ["80", "443"]

- IPProtocol: icmp

sourceRanges: ["10.0.0.0/24"]

networkRef:

name: example

providerConfigRef:

name: example

You can of course use configuration generators like CUE or jsonnet but these aren’t the primary authoring mechanism and you’re largely on your own if you choose this route.

What I find interesting about the configuration based authoring experience from Crossplane is that due to the complex nature of the Kubernetes spec and the use of custom resources, the authoring experience has quite a learning curve. It’s not a simple case of throwing some resources into a file, you have to flesh out the manifest in a way that meets the Kubernetes API definition, so it can be a little daunting at times.

Of course, the experience isn’t as steep as a DSL or programming language, but it’s not “easy”.

Deployment Experience

Crossplane’s primary value driver is the fact the execution experience leverages the Kubernetes reconciliation loop to manage resources. You send off your Kubernetes manifest to the Kubernetes cluster running the crossplane controller and it will go and provision cloud providers resources for you - handling all the backoff mechanisms and driving towards a desired state.

The big issue with this is that you need a whole goddamn Kubernetes cluster before you can do anything. You can use the Upbound SaaS service, but you need to give them cloud provider credentials for it to be able to do anything. You can stand up a small Kubernetes cluster manually and install Crossplane as well, but isn’t that sorta why Infrastructure as Code is for?

People who are deeply invested in the Kubernetes ecosystem love Crossplane. I just don’t see it myself.

Cloud Provider Experience

The crossplane marketplace has providers for the major clouds, but the landscape is relatively scarce. You won’t find support for popular clouds like Digital Ocean in the marketplace even though there is contributor based support

Crossplane supports bridging Terraform providers from its Terrajet tool, but it’s in its infancy.

Azure Resource Manager

Azure Resource Manager, or “ARM” as it’s commonly known, it’s Azure’s Infrastructure as Code tool. It acts as well documented and thorough API, but also offers some server side execution as well. Let’s have a look.

Authoring Experience

The default authoring experience with ARM is a configuration language experience. Most ARM templates come in the form of YAML documents, but as with most configuration language based experiences you can define the template using generators, although I rarely see it in the wild.

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentTemplate.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"storagePrefix": {

"type": "string",

"minLength": 3,

"maxLength": 11

},

"storageSKU": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "Standard_LRS",

"allowedValues": [

"Standard_LRS",

"Standard_GRS",

"Standard_RAGRS",

"Standard_ZRS",

"Premium_LRS",

"Premium_ZRS",

"Standard_GZRS",

"Standard_RAGZRS"

]

},

"location": {

"type": "string",

"defaultValue": "[resourceGroup().location]"

}

},

"variables": {

"uniqueStorageName": "[concat(parameters('storagePrefix'), uniqueString(resourceGroup().id))]"

},

"resources": [

{

"type": "Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts",

"apiVersion": "2021-09-01",

"name": "[variables('uniqueStorageName')]",

"location": "[parameters('location')]",

"sku": {

"name": "[parameters('storageSKU')]"

},

"kind": "StorageV2",

"properties": {

"supportsHttpsTrafficOnly": true

}

}

],

"outputs": {

"storageEndpoint": {

"type": "object",

"value": "[reference(variables('uniqueStorageName')).primaryEndpoints]"

}

}

}

Interestingly, Azure also offers its own DSL specifically for ARM templates in the form of bicep. Like all other DSLs, it’s got a single use - generating ARM templates.

@minLength(3)

@maxLength(11)

param storagePrefix string

@allowed([

'Standard_LRS'

'Standard_GRS'

'Standard_RAGRS'

'Standard_ZRS'

'Premium_LRS'

'Premium_ZRS'

'Standard_GZRS'

'Standard_RAGZRS'

])

param storageSKU string = 'Standard_LRS'

param location string = resourceGroup().location

var uniqueStorageName = '${storagePrefix}${uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)}'

resource stg 'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts@2021-04-01' = {

name: uniqueStorageName

location: location

sku: {

name: storageSKU

}

kind: 'StorageV2'

properties: {

supportsHttpsTrafficOnly: true

}

}

output storageEndpoint object = stg.properties.primaryEndpoints

Execution Experience

The ARM execution experience is server side, you submit your template (either configuration authored or bicep authored) and ARM handles building the graph and executing the resources in the required order.

Similarly to CloudFormation, you have no control over the speed of this and no ability to manipulate or change the way the execution is handled. It’s a much simpler mechanism than a client side driven execution experience, but lacks a lot of the flexibility you might need.

Cloud Provider Experience

ARM is Azure only, and to my knowledge has no ability to manage resources outside Azure. So, that’s that really. If you’re Azure only, ARM is valid. If you need anything else, it’s not.

Pulumi

Pulumi is the Infrastructure as Code tool which pioneered the programming language based authoring approach. The company was founded in 2018 and has been innovating in the Infrastructure as Code space ever since.

Authoring Experience

As I previously mentioned, Pulumi was the OG tool that introduced a programming language based authoring experience. It started with TypeScript and JavaScript support, but has since added Python, DotNet, Go, and Java as supported languages.

What’s unique about Pulumi is that, unlike the programming language authoring experience offered by the CDK supported suite of tools, Pulumi does not generate an intermediary document. This creates a bunch of useful scenarios, such as the ability to import any library or SDK for the respective language and leverage it inside the Pulumi program. A great example is this snippet which allows you to create custom waiters and healthchecks with the Kubernetes client API.

// define an EKS cluster

const cluster = new eks.Cluster(name, {

providerCredentialOpts: kubeconfigOpts,

vpcId: vpc.id,

privateSubnetIds: vpc.privateSubnetIds,

publicSubnetIds: vpc.publicSubnetIds,

instanceType: "t2.medium",

desiredCapacity: 2,

minSize: 1,

maxSize: 2,

createOidcProvider: true,

tags: {

Owner: "lbriggs",

owner: "lbriggs",

}

});

Like any other programming language based experience, you get the full support of the IDE and language’s type system but you obviously have to be familiar with the language ecosystem and toolchain.

In addition to a programming language based experience, Pulumi also supports a configuration language based experience with Pulumi YAML

name: yamldemo

runtime: yaml

resources:

bucket:

type: aws:s3:Bucket

properties:

website:

indexDocument: index.html

index.html:

type: aws:s3:BucketObject

properties:

bucket: ${bucket.id}

content: <h1>Hello, world!</h1>

contentType: text/html

acl: public-read

outputs:

url: http://${bucket.websiteEndpoint}

You can use generators like CUE for this as well (and you can also get a little bit wild with it, as I’ve posted before).

Uniquely, Pulumi has support for improving the IDE experience for its configuration language authoring model via a language server plugin, which is usually reserved for DSLs or programming languages. This means you can get all the benefits of the shallower learning curve but some of the benefits of the DSL or programming language based authoring experiences.

The final unique element to Pulumi’s configuration language based experience is that it allows you to “eject” to a programming language based experience once you’ve gotten tired of it. You can simply run pulumi convert --language and the Pulumi YAML program will be converted to the language of your choice, bringing you all the benefits like increased flexibility.

Execution Experience

The Pulumi execution experience is client side, meaning you have to provide credentials to the Pulumi CLI and provider in order for it to create resources. You author your Pulumi program, then run the Pulumi CLI to let the cloud provider know about it.

Do you want to perform this update? yes

Updating (dev)

View Live: https://app.pulumi.com/jaxxstorm/s3/dev/updates/9

Type Name Status

+ pulumi:pulumi:Stack s3-dev created

+ ├─ aws:s3:Bucket my-bucket created

+ └─ aws:s3:BucketPolicy bucketPolicy created

Resources:

+ 3 created

Duration: 7s

What’s unique about Pulumi’s client side experience is that it can be embedded into any mechanism through Pulumi’s Automation API. This gives you the ability to essentially chose your own workflow for the client side drive experience. You can embed Pulumi into your own custom command line tools (and abstract the entire workflow that would usually be run in a series of CI/CD pipeline steps for example) or embed Pulumi into a web server creating your own server side execution experience.

If you’re a platform team thinking about the best ways of meeting your users needs, this give you an incredible level of flexibility that isn’t really possible with any of the other tools.

Cloud Provider Experience

Pulumi’s supports a whole bunch of cloud providers and you can find them in the Pulumi Registry. There are “bridged” providers which use Terraform providers to map out the CRUD functions available for each API on the cloud provider, or “native” providers which map out the functions directly from the Cloud Provider API. Native providers often have features available before bridged providers due to them not requiring community or code contributions before being usable, but it’s down to the cloud provider to add those mechanisms to their respective APIs - Azure is very good at this for example, AWS has some work to do.

Making the choice

Okay, I’ve written a lot of words so far explaining what the options are and how they can help you, but the title of this post has “choosing” in it, so I probably need to help you decide.

The Infrastructure as Code Decision Tree

Taking all of the considerations around execution, authoring and cloud provider experience, I’d like to introduce to you - the Infrastructure as Code Decision Tree

This doesn’t cover all of the experience, but I hope it helps you make the right decisions.

The right decision is of course to choose Pulumi, but I’ll let you, reader, figure that out on your own!

© 2021, Ritij Jain | Pudhina Fresh theme for Jekyll.