#devops #infrastructure-as-code #declarative #imperative

Why does nobody seem to know what imperative and declarative actually mean?

Published Jul 20, 2022 by Lee Briggs

Like all tech employees, I’ve had feedback and performance reviews my whole career which varied from “you’re doing a great job” to “Stop. Just stop doing that”. I like to believe there are things I’ve addressed, and like all human beings there are things I’ll continue to work on and never really get the hang of.

One piece of feedback I’ve had my entire career is that I “care too much”. Now, this isn’t like one of those awful interview question responses where someone says “they’re too hard-working” or they’re “too much of a perfectionist” - it’s very valid feedback that I desperately need to address.

I loved @ConHome question to Tory candidates about their greatest weakness. @RishiSunak is way too diligent, @trussliz is too enthusiastic, @TomTugendhat is too loyal to the army, @PennyMordaunt is too much of a team player and @KemiBadenoch is way too funny. Such self knowledge!

— Robert Peston (@Peston) July 15, 2022

What I believe people actually mean when they tell me I care too much is that I concern myself with things outside the scope of my day-to-day job. My job at Pulumi is to help potential customers see the value in the product and existing customers be successful. As a result, I see a lot of naysayers and objectionists who truly believe that Pulumi is just wrong in the same way pineapple on pizza is wrong. A lot of this is just par for the course: not everyone is going to love your product and appreciate it (altough, our customers overwhelmingly seem to!).

My job description does not expect me to continuously argue with people on the internet about what words mean. To my detriment, I just cannot stop when it comes to one particular topic.

The problem is, while it’s not important to my job, I find myself consistently arguing with people about it because it’s just completely wrong. Not only are people consistently wrong about it, but when challenged they will often double-down, instead of even considering the idea they’re not correct. It wouldn’t usually matter, but like all inaccuracies in this post-truth world, the idea then spreads and becomes a misconception that leads to FUD when I’m having conversations with customers about Pulumi, at which point I sigh and have the same conversation again.

If you didn’t skip over the title, you probably already know what I’m talking about, but the topic at hand is:

Nobody seems to know what the fuck the words “imperative” and “declarative” actually mean.

It’s imperative we address this

When talking about infrastructure as code, you’ll often hear the term “declarative” very early in the conversation. As I’ve said multiple times before, we as an industry have essentially settled on the idea that any infrastructure as code tool, to be worth your consideration, must be declarative.

What you often see in conversations about Terraform, Pulumi, and AWS CDK is the idea that Terraform is “better” than AWS CDK and Pulumi because it’s declarative while Pulumi and CDK are imperative.

This is completely fucking incorrect, but it happens all the goddamn time.

You’re overexaggerating. It doesn’t happen that often..

Oh no. You’re wrong. It happens constantly.

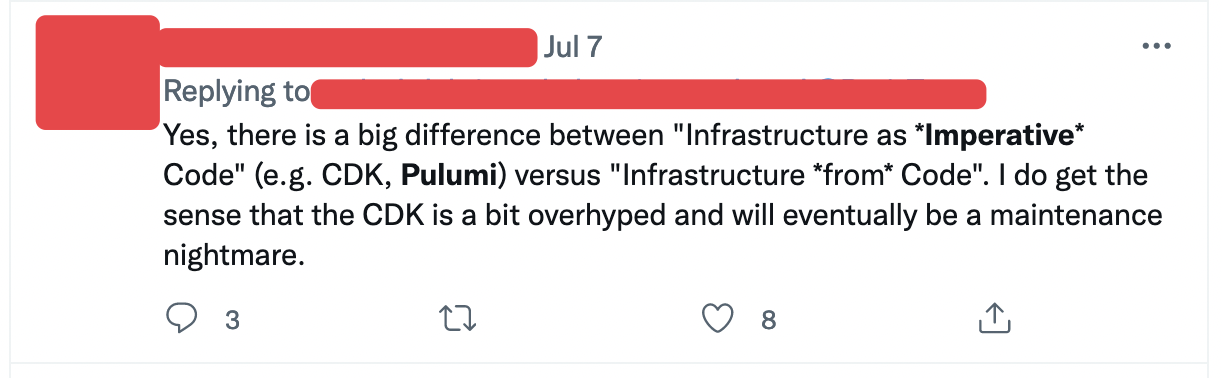

It happens on Twitter (feel free to search for the words “pulumi” and “imperative” together for more like this):

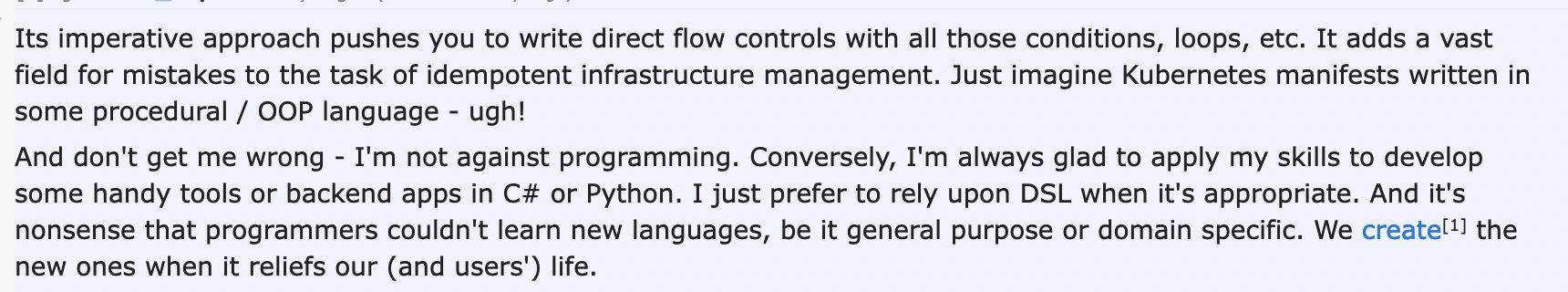

It happens on Reddit:

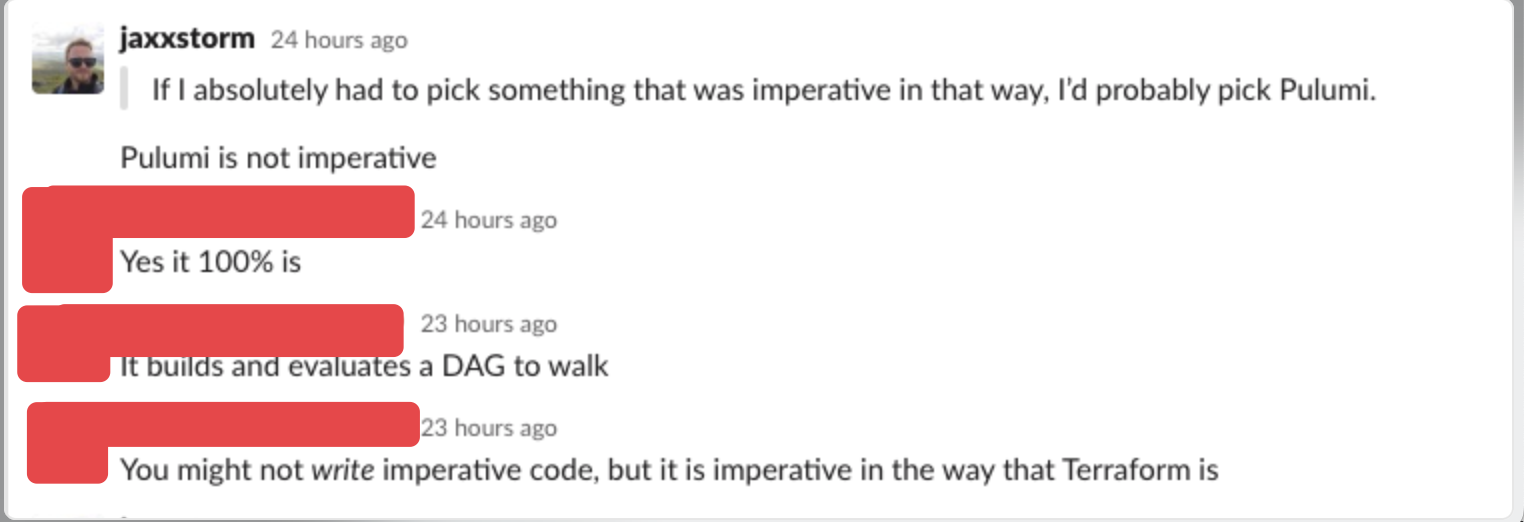

You see it in very popular and large Slack communities devoted to DevOps

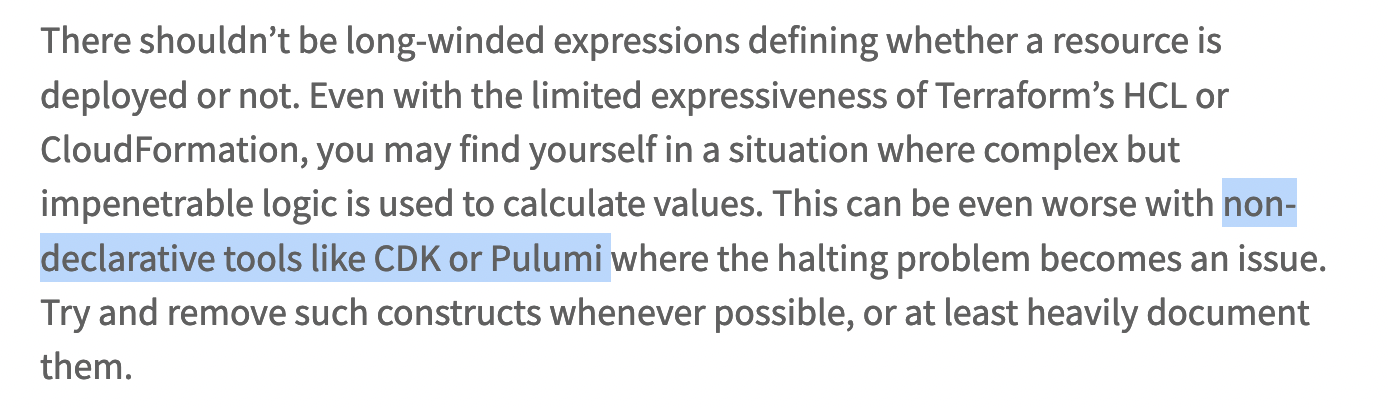

You can even see it on blog posts by engineers with professional certificates at well-regarded consulting organizations:

There are even YouTube videos with thousands of views saying the same thing.

I want to start by stating that I understand why people make this mistake. I get it. It doesn’t make the situation any less frustrating. You might be thinking at this point “you’re emotionally invested in this, you work at Pulumi” and in many ways you’re right, but the same incorrectness is thrown at AWS CDK, Terraform CDK - anything that uses an imperative language for its authoring experience.

Now, before you hold up your hand and say “you just said it uses an imperative language for its authoring experience, you’re arguing against yourself now!” let’s examine the situation before you ride off on your high horse.

“We demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!”

Before we examine how we got here, let’s start with some basics: the definitions of imperative and declarative.

Now, if you really want, you can go and read the wikipedia definition of imperative and declarative. If you don’t have time for that or don’t want to get sucked into an impromptu session of the Wikipedia Game with yourself, I’ll provide my own quick high-level definitions.

At their core, imperative and declarative differ in one major and fundamental way. Imperative has control flow and declarative does not.

In practice, this is very easy to spot. If your program has statements in it which define if something will happen, checks for errors, and verifies if something was successful, it has control flow.

You can see an example of this in any infrastructure-related program using one of the cloud provider SDKs. If you try to create something using AWS’s boto3, you can see an imperative model in action:

import boto3

from botocore.exceptions import ClientError

# try create an IAM user

try:

iam = boto3.client('iam')

user = iam.create_user(UserName='fred')

print("Created user: %s" % user)

except ClientError as e: # if we have an error, we need to check the error state and return information to the user

if e.response['Error']['Code'] == 'EntityAlreadyExists':

print("User already exists")

else:

print("Unexpected error: %s" % e)

This is a very small example. In larger applications, the amount of control flow you end up performing can be incredibly unwieldy and get quickly out of control. To give you an idea of this, take a look at the code here in eksctl, an (excellent) imperative tool that allows you to create Amazon EKS clusters. You might notice that many of these methods are just there to check the condition of things and determine the current state of the cluster. These validation methods are all necessary because of the imperative nature of the tool, they require control flow along the lines of:

if cluster_exists:

echo "you already created that cluster"

else:

echo "I'm creating a cluster for you"

Declarative tools on the other hand require none of this. In Terraform’s HCL for example, you just..define the cluster. Terraform takes care of all the control flow logic in its engine, you don’t have to do any checking at all:

resource "aws_eks_cluster" "example" {

name = "example"

role_arn = aws_iam_role.example.arn

vpc_config {

subnet_ids = [aws_subnet.example1.id, aws_subnet.example2.id]

}

}

If you’re completely new to infrastructure as code, let me tell you, the declarative nature of infrastructure as code tools dramatically reduces the amount of code you write, reduces the number of errors you run into, and generally makes your life dealing with the idiosyncrasies of cloud APIs a lot better.

Okay, you’ve defined the terms. What else is going on?

The problem seems to stem from the Terraform community. Unless I’m mistaken, Terraform was the first tool to drive home the importance of defining infrastructure declaratively. CloudFormation came first, but when Terraform came along, lots of people sat up and took notice. Terraform’s DSL, HCL, allows users to define infrastructure with a configuration language that doesn’t allow you to define real conditionals and control flow. As I mentioned in the last paragraph, you simply state how you want your infrastructure to look in HCL, and Terraform handles all the logic for you.

Terraform (and CloudFormation, but to a lesser extent) making use of a declarative engine while also using a configuration language for its infrastructure definitions appears to have created a situation where people consider anything defined in a configuration language “declarative”.

I cannot state this more clearly, so if you could imagine me clearing my throat before yelling this.

If you think something using a configuration language makes something declarative, you are wrong.

The power of a graph

Creating a declarative tool is not easy. The temptation might be to write something that abstracts the imperative calls from the user, but the smart people who built and designed infrastructure as code solutions came up with a better approach.

Instead of trying to catch and try all of the errors ever, they went ahead and made use of a mathematical concept to ease the situation.

They started to use a DAG, or a directed acyclic graph.

Hold on poindexter, what the hell is a DAG?

Well, I’ll start by saying I’m not a mathematician (side note: I got my calculator out yesterday to add a 20% tip for dinner, not my proudest moment) but I do have a very general idea of what a DAG is.

The simplest and best way to break down what constitues a “DAG” is to examine each word on its own. I’ll shamelessly steal from this StackOverflow answer as it does a way better job of defining it than I ever could.

- graph = structure consisting of nodes, that are connected to each other with edges

- directed = the connections between the nodes (edges) have a direction: A -> B is not the same as B -> A

- acyclic = “non-circular” = moving from node to node by following the edges, you will never encounter the same node for the second time.

If you put this into the concept of infrastructure as code tool whether that be in Terraform, Pulumi, CloudFormation, CDK, or any other declarative tool you can think of it like this; each of the “resources” you’re defining in the program is a node. Any dependencies between those nodes (for example, the S3 Bucket Policy requires the S3 Bucket to exist) are directed and finally, you cannot create a circular dependency because the tool will yell at you.

To drill down just a little bit, if you imagine an infrastructure as code program that defines an S3 bucket and an S3 bucket policy. The bucket policy cannot be created until the S3 bucket itself exists, otherwise, where would you attach the policy? That’s a directed edge, we’re saying S3 Bucket -> S3 Bucket Policy.

Terraform makes this very very easy to understand because of its configuration language authoring experience, but Pulumi, AWS CDK, and other infrastructure as code programs do exactly the same thing.

Not only do Pulumi and Terraform build a graph for you, but they also allow you to examine the graph that’s built! Pulumi has the pulumi stack graph command and Terraform has the terraform graph command.

This graph is built when you’ve authored your Terraform or Pulumi program and is then executed by the respective tool’s engines that idempotently walk that graph on each tool instantiation.

Whoa, slow down there, what’s this idempotent word that’s come out of nowhere?

Idempotent is another key part of any infrastructure as code tool that originated from the configuration management tools you know and love like Puppet, Chef, CfEngine, and Ansible.

Idempotent just means that if you run the same thing over and over again you can expect to get the same results. Every infrastructure as code tool (unless I’ve missed one) is declarative and idempotent. Configuration management tools are generally idempotent, but not necessarily declarative. I’ll come back to that in a few moments

I think I get it. Why do people think Pulumi and CDK are imperative then?

The simple answer here seems to be: they aren’t thinking of the tool, they’re thinking of the language being used for the authoring experience.

Configuration languages make declarative states easy to grasp because you can’t use conditionals in configuration languages without bolting on a templating language or making big changes to a DSL.

With Pulumi and AWS CDK however, you can use conditionals to your heart’s content because they use imperative languages as their primary authoring experience.

Take the following snippet of Pulumi code as an example:

const isMinikube = config.require("isMinikube");

// Allocate an IP to the nginx Deployment.

const frontend = new k8s.core.v1.Service(appName, {

metadata: { labels: nginx.spec.template.metadata.labels },

spec: {

type: isMinikube === "true" ? "ClusterIP" : "LoadBalancer", // imperative code!

ports: [{ port: 80, targetPort: 80, protocol: "TCP" }],

selector: appLabels,

},

});

Here, you can see we’ve defined a boolean condition isMinikube and then we’re making decisions for how we construct the resources using a ternary operator.

There is no way for me to argue that this isn’t an imperative operation because it is. If you’re thinking; “here’s that imperative word again with Pulumi” then let me tell you this:

While the operation of checking the value of isMinikube is indeed imperative, the result is still declarative. What does this mean?

Pulumi as a tool is declarative. It’s the language you’re using to write things that’s imperative, not Pulumi itself.

An imperative graph

When you use conditionals in AWS CDK, Terraform CDK, Pulumi, or any other infrastructure as code tools that might see the light and realize imperative languages are just superior to configuration languages, you are still building a DAG. What the imperative authoring experience gives you is the ability to manipulate how the DAG is built.

You’re still building a graph. You’re not checking if the operation was successful or unsuccessful because that would mean the tool is imperative. Remember, an imperative way of creating an S3 bucket is something like this:

if s3_bucket_created:

echo "go ahead and create the policy now"

Pulumi is handling all of this logic for you with its declarative nature, here’s the code for creating an S3 bucket and policy in Pulumi’s TypeScript:

// create the S3 bucket

const example = new aws.s3.BucketV2("example", {});

// define a bucket policy

const allowAccessFromAnotherAccountPolicyDocument = aws.iam.getPolicyDocumentOutput({

statements: [{

principals: [{

type: "AWS",

identifiers: ["123456789012"],

}],

actions: [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:ListBucket",

],

resources: [

example.arn,

pulumi.interpolate`${example.arn}/*`, // we're passing the bucket arn to the policy

],

}],

});

// now attach the bucket to the policy

const allowAccessFromAnotherAccountBucketPolicy = new aws.s3.BucketPolicy("allowAccessFromAnotherAccountBucketPolicy", {

bucket: example.id,

policy: allowAccessFromAnotherAccountPolicyDocument.apply(allowAccessFromAnotherAccountPolicyDocument => allowAccessFromAnotherAccountPolicyDocument.json),

});

There are no if statements here. We aren’t checking for success or failure, we’re not using try/catch or any other mechanism. Pulumi is doing it declaratively.

Imperative workarounds

People using Terraform often still want to manipulate the graph the Terraform builds, but Terraform HCL lacks some of the control flow that allows you to do this easily. There are some imperative mechanisms, such as the count meta argument which is hijacked and used as a conditional constantly in Terraform modules:

count = var.enabled ? 1 : length([some list of resources or datasources])

This is functionally the same as the ternary operator seen in the earlier Pulumi example except it’s hard to read and understand because it’s not an if statement, it’s a count statement.

Terraform also has the for_each meta argument which again, allows you to manipulate the graph that is built to loop through results and create resources that can change depending on conditions from elsewhere.

Imperative languages just give you the flexibility you bloody need to manipulate the way the graph is built.

If you’re still not convinced at this stage, let me finish with these two points.

If configuration languages are declarative…

If configuration languages are the only true way to be declarative, let’s take a look at Ansible for a second. Ansible playbooks are written in YAML, inarguably a configuration language. However, Ansible allows you to have control flow in its definitions:

tasks:

- name: Shut down CentOS 6 and Debian 7 systems

ansible.builtin.command: /sbin/shutdown -t now

when: (ansible_facts['distribution'] == "CentOS" and ansible_facts['distribution_major_version'] == "6") or

(ansible_facts['distribution'] == "Debian" and ansible_facts['distribution_major_version'] == "7")

This is nice and useful for a configuration management tool because you’re probably dealing with lots of different use cases and issues, whereas dealing with APIs like an infrastructure as code tool does is a lot more rigid. Nobody is blaming ansible for this, but if your definition of declarative is “MuH CoNFiguRatioN LanguaGe” then you’re going to have a hard time explaining how Ansible isn’t declarative.

If you’re still really really stuck on this idea, allow me to introduce you to Pulumi YAML

name: webserver

runtime: yaml

description: Basic example of an AWS web server accessible over HTTP

configuration:

InstanceType:

type: String

default: t3.micro

variables:

ec2ami:

Fn::Invoke:

Function: aws:getAmi

Arguments:

filters:

- name: name

values: ["amzn-ami-hvm-*-x86_64-ebs"]

owners: ["137112412989"]

mostRecent: true

Return: id

resources:

WebSecGrp:

type: aws:ec2:SecurityGroup

properties:

ingress:

- protocol: tcp

fromPort: 80

toPort: 80

cidrBlocks: ["0.0.0.0/0"]

WebServer:

type: aws:ec2:Instance

properties:

instanceType: ${InstanceType}

ami: ${ec2ami}

userData: |-

#!/bin/bash

echo 'Hello, World from ${WebSecGrp.arn}!' > index.html

nohup python -m SimpleHTTPServer 80 &

vpcSecurityGroupIds:

- ${WebSecGrp}

UsEast2Provider:

type: pulumi:providers:aws

properties:

region: us-east-2

MyBucket:

type: aws:s3:Bucket

options:

provider: ${UsEast2Provider}

outputs:

InstanceId: ${WebServer.id}

PublicIp: ${WebServer.publicIp}

PublicHostName: ${WebServer.publicDns}

There you go. It’s declarative now. I hope you’re happy.

© 2021, Ritij Jain | Pudhina Fresh theme for Jekyll.